One of my favourite video games as a child was Super Mario Galaxy. It was my first ‘real’ video game, played on the Wii, and I was enthralled by the clever puzzles and levels Mario navigated with impressive jumps and flips over lava and quicksand.

Disclaimer: I have never worked for Nintendo, and therefore have no idea how they actually created gravity in Super Mario Galaxy. This post is merely my attempt to replicate the feel in a practical way.

As I grew older I learnt 3D modelling and programming for various personal and academic projects. The pull of video games was still there, but now I had the understanding and context around how software and assets are made. I felt compelled to figure out what made Super Mario Galaxy tick, and why it is so special.

So what is so difficult about this style of gravity then? There is an interesting, but inaccurate, Youtube video attempting to explain it. In the video, it states that the character will perform a raycast “from his feet” every frame, which is used to find the surface normal of the planet below. This surface normal, a vector, then defines what the current “up” vector is for the character in the current frame. While this does work in specific situations in the general case it is inefficient and inaccurate.

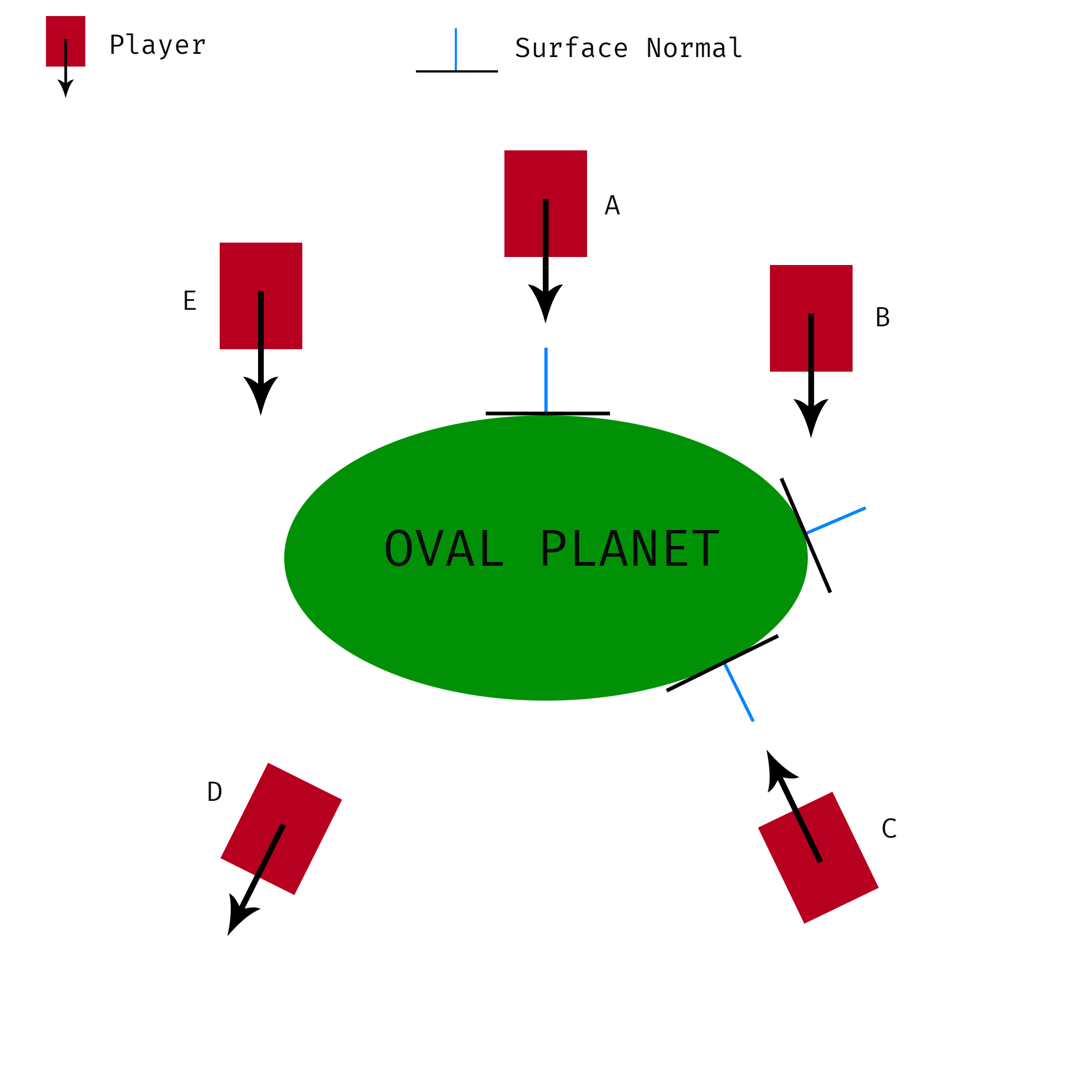

To illustrate why, imagine that the player jumps and moves around a small planet:

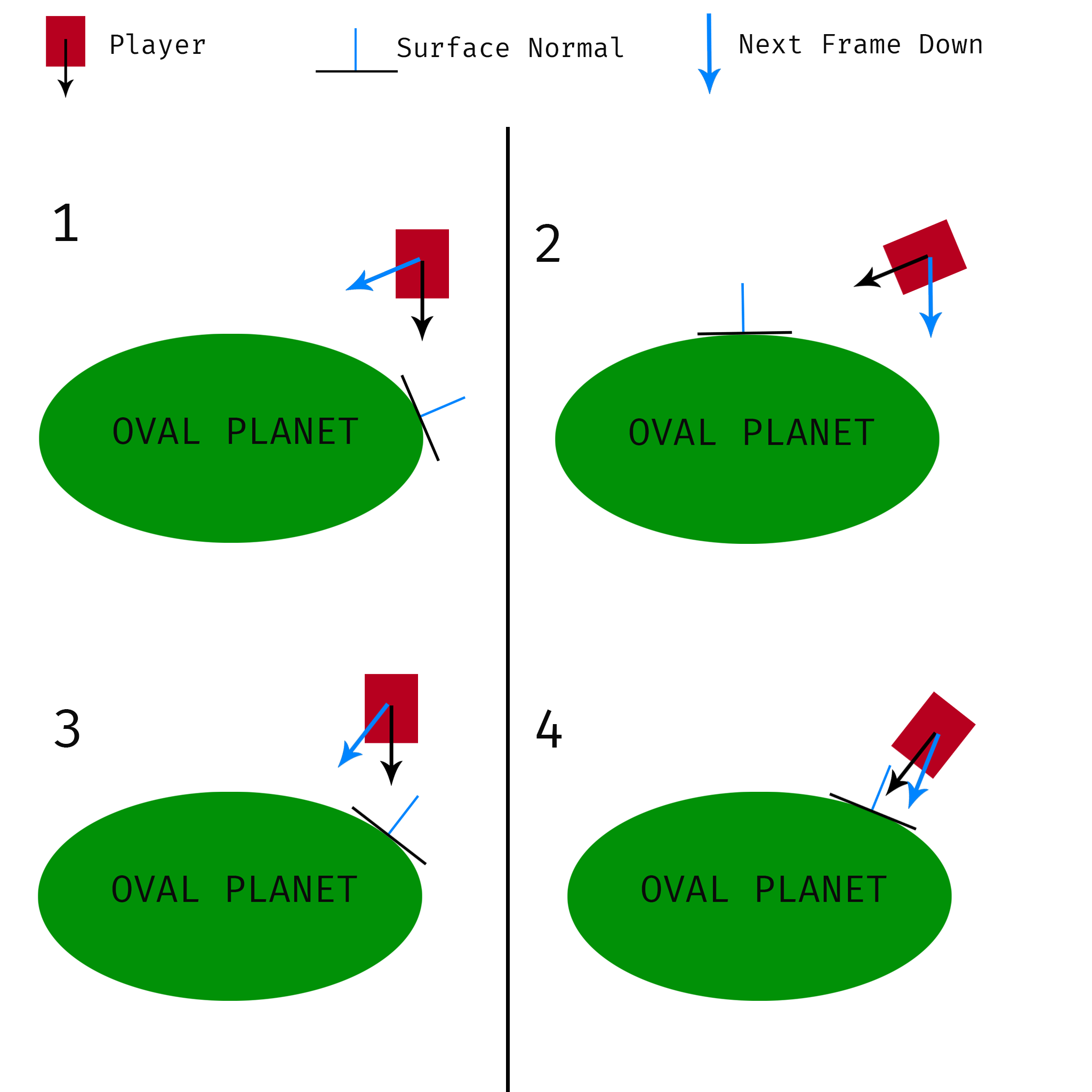

As you can see, for the character at position A and C this ray cast method works fine, but only because they are already pointing towards the planet. Character B is going to have a hard time, because the surface normal it detects will try to rotate the player to a surface it wouldn’t land on, flipping back and forth until it converges on a single point:

You could argue this can be fixed by interpolating the rotation across multiple frames or performing a recursive raycast until the point converges, but this still isn’t perfect and quite complicated. It is also important to bear in mind that this is a simple example; the question mark planet from Super Mario Galaxy is a much more complex example.

Because the “feet” of the player are relative to its current rotation, if it’s facing away from the planet it will have no ground information. Characters D and E both have this problem. D is completely facing the wrong way (say if it is jumping from another planet) but E just misses the planet, maybe even colliding with it, but still falling away from it. None of this accounts for gravity zones or rotating platforms, which is required for an advanced game.

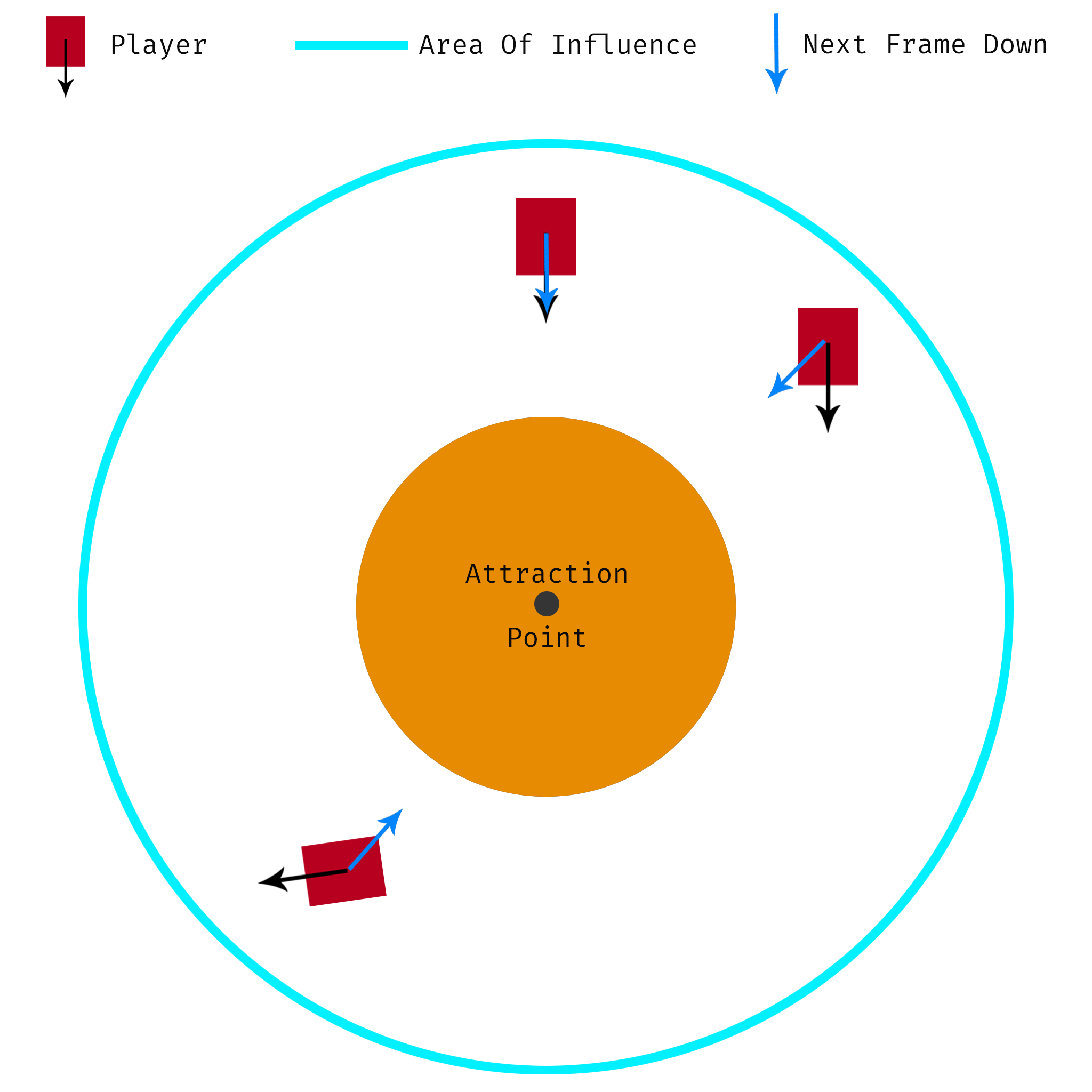

How, then, does Super Mario Galaxy perform this feat of perfect gravity? Well, it turns out that it takes a mathematical approach. The primary problem with a ray cast is that it’s dependent on the orientation of the player. What we need is some way of finding the correct gravity direction from only the player’s position.

Let’s explore a simple example: a spherical planet. To find the direction of gravity we don’t need the geometry of a sphere, we can just find the vector pointing from the player’s position to the centre of the sphere:

In practice this looks something like this:

FVector GravityDirection = (AttractionPoint - PlayerPosition).GetSafeNormal()

This is fairly straightforward, but there are more than just spheres in Super Mario Galaxy. What about the cylindrical planet in Space Storm Galaxy?

You might think we need to revert to the raycast method, but we can actually do something clever. There is a mathematical formula for finding the closest point on a line segment, using vectors and dot products. Fortunately, most programming maths libraries have a built-in function to do it for you. In Unreal:

FVector AttractionPoint = FMath::ClosestPointOnLine(PointOne, PointTwo, PlayerPosition);

You can then use the same formula as the spherical planet to find the gravity direction. Neat!

“Nah mate, that’s not enough,” you say. “What about the really crazy planets, like the question mark planet from Gusty Garden Galaxy?”

Aha, well, this is just an extension of the previous solution, as this is a curvy cylinder. And what is a curvy ’line segment’? A spline! In fact, most spline implementations have a FindClosestPoint(...) or similar function, and we can use the same method as for the line segment. UE4 has a USplineComponent

which works wonderfully:

FVector AttractionPoint = Spline->FindLocationClosestToWorldLocation(PlayerPosition, ESplineCoordinateSpace::World);

That’s it for now! There are a few other mathematical gravity definitions that I’ll cover in a later post.

What creative solutions have you come up with to solve gravity problems? Let me know by leaving a comment!